Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Vallotton: One of Art’s Greatest Over-Achievers

Félix Vallotton is perhaps the chameleon of the Nabis era. With a traditional start in academic and portrait painting, Vallotton mastered printmaking, portrait painting, wood engraving, Nabis-style genre scenes and nudes, and then moved on to Realism before leading the way for the New Objectivity movement. He did not stop at painting, however, but tried his hand at writing no fewer than eight plays and three novels. Whilst these may not have been the most significant or even best-selling tomes of their time, it was still a remarkable achievement. After adding landscapes, still life painting, and sculptures to his already impressive repertoire, the resulting impression of this artist is that he was not only a style chameleon, but a fantastic over-achiever.

But why was Vallotton so eager to try his hand at so many different mediums, styles, and genres? Could it be that he was simply overdosing on coffee, or was he, in fact, trying to carve out a niche for himself in a highly competitive environment? It can absolutely be acknowledged that he succeeded in doing this, for certain with his work amongst the Nabis, and also in his eventual expertise in woodcuts. Why then continue adapting and reworking what he had already come to master? In all of his trials, successes, and celebrity, one theory is that Félix Vallotton never truly found the voice that he felt that he should have. In this quest to achieve perfection, he may certainly have acquired a great deal of prowess working in certain fields, but there was always a ‘next goal’. Something bigger, something better, and something to be strived for. In this lies the key to innovation and great artistic breakthrough. While many are happy settling with a success they have achieved, it is the Steve Jobs, Albert Einsteins, and Mark Zuckerbergs of this world who step beyond that to not only ask for success, but to revolutionise. Within this group, Vallotton has definitely earned his place.

For your chance to catch a rare glimpse of some of Vallotton’s elusive artworks, hidden for years in private collections, get yourself over to Zurich! The Kunsthaus, Zurich, is hosting Félix Vallotton. Precious Moments, an exhibition combining the gallery’s own impressive collection with those of private collectors, running until the 15th September. If you really can’t make this exciting exhibition, go ahead and grab a copy of the new Félix Vallotton by Nathalia Brodskaïa.

- Fiona Torsch

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Impressionist, and proud

The Impressionists came to be known as such after a 10-year battle for recognition. In 19th-century France, artistic esteem could only be attained by recognition by the Academy of Fine Arts and the displaying of their artwork in the Salons, or yearly exhibitions in Paris. This new art movement was too mind-blowing for those stuffy old codgers – Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass didn’t make the grade because of the daring inclusion of a stark-naked lady frolicking at a picnic. I can’t imagine what they would make of Prince Harry’s trip to Las Vegas…

Reconstruction of Prince Harry’s trip to Vegas…

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, 1863.

Oil on canvas, 208 x 264.5 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

A brief glimmer of hope came in 1863 when Napoleon III, shocked by the quality artwork that was being sidelined, opened an exhibition alongside the official Salon, an Exhibition for Rejects. This group of artists received more visitors than the official Salon, but most came along for a good chuckle at these deluded ‘artists’ and their strange paintings. Requests for another exhibition were denied, until in 1874 they decided to take matters into their own hands…

Thirty artists including Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Cézanne, Degas and Morisot participated in a private exhibition, which was still too zany for many. Louis Leroy wrote a sarcastic, satirical review, coining the term ‘Impressionists’ as a play on words of the title of Monet’s painting Impression, Sunrise. The term caught on, and what was meant to be a moniker of derision became a badge of honour for the group. And Leroy must have been laughing on the other side of his face when Impressionism spread beyond France, paving the way for Modern art, and even becoming the long-lasting legacy of 19th-century French art.

So take a leaf out of the Impressionists’ book and wear those insults with pride. My suggestions for some topically beleaguered individuals include: Prince Harry – ‘The Naked Prince’, Todd Akin – ‘The Legitimator’, and I’m sure Julian Assange could put a positive spin on ‘coward’, ‘tool’ or ‘cyber terrorist’.

Sweden’s Nationalmuseum has an exhibit dedicated to 19th-century France and the beginning of the Modern era, until 3 February 2013. If you would like to read more about the peppy Impressionists, try this impressive art book or compact gift version, written by Nathalia Brodskaya.

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Caillebotte: Sugar Daddy of Impressionism

Although classified as an Impressionist, Caillebotte’s style clearly differs from his counterparts such as Degas, Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro with whom he displayed his works at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876. Many—myself included--consider him more of a Realist than an Impressionist. Due to Caillebotte’s passion for photography, his paintings often resemble photographs, capturing a single, fleeting moment in time quite realistically.

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street, Rainy Day, 1877.

Oil on canvas, 212 cm x 276 cm.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

Like his contemporaries, Caillebotte captured images of a rapidly changing Paris, the result of Napoleon III and Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann's urban renewal project. Beautiful, tree-lined boulevards, green spaces and gardens, and modern public facilities arose, paving the way for the beautiful, dreamy Paris we all know today. However, unlike his fellow Impressionists, Caillebotte attempted to depict the new Paris in a more realistic way; his paintings often create a feeling of alienation and sorrow (Paris Street, Rainy Day, above). For him, the new metropolitan city, with its meticulously planned layout and design, was something like a SimCity—perfect from the outside, lonely from the inside.

Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers, 1875.

Oil on canvas, 102 cm x 146.5 cm.

Musée D'Orsay, Paris.

Caillebotte is also known for introducing a new subject matter: the urban working class. As a result of the new railway and the Industrial Revolution in France (1815-1860), there was a huge migration of workers from the countryside to Paris. This new social class, la class ouvrière or the working class, became a fascination of Caillebotte’s. However, up to this point, the only portrayals of working-class life had been of peasants and farmers from the countryside. Hence, it came as no surprise that the Salon rejected The Floor Scrapers (above) in 1875, deeming it vulgar and offensive. They simply did not want to accept the reality—the sorrow, the poverty, and the brutal working conditions—of their new and improved Paris that Caillebotte so desperately wanted to portray through his work.

Want to see Caillebotte’s works and some outstanding photography from the late 19th and early 20th centuries? Head over to Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt between 18 October 2012 and 20 January 2013 for their exhibit Gustave Caillebotte. An Impressionist and Photography. You can also check out our ebook on Impressionism by Nathalia Brodskaya to learn more.

Follow us on Twitter and Pinterest

Like us on Facebook

Monday, September 10, 2012

The Secret to Being a Great Artist…

What factors contributed to this artist’s greatness?

Could it be an inherent talent? He was born into a creative family and immersed in an artistic environment from childhood; indeed, both his parents were famous composers.

Or, could it be his drive and his determination to succeed? There’s no doubt that Serov was a hard worker and a competitive artist, who strove to be at the forefront of the new artistic movements of his generation. He worked tirelessly to perfect his drawing skills and painted everything he could lay his eyes on.

What about his passion for the works of the greats? He began, at a formative age, to pay attention to the “‘high craftsmanship’ that characterised the Old Masters” which “led him to understand what an artist should aspire to”, inspiring him to go perfect his technique and create technically excellent pieces of art.

Although these factors surely had an impact on the artist himself, they are representative of many talented and determined artists, so what was it that made Serov stand out?

Valentin Serov, Girl with Peaches. Portrait of Vera Mamontova, 1887.

Oil on canvas, 91 x 85 cm.

The State Trekyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Valentin Serov, Sunlit Girl. Portrait of Maria Simonovich, 1888.

Oil on canvas, 89.5 x 71 cm.

The State Trekyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Serov was extremely privileged in his upbringing, benefiting from his parents’ hospitality; “The Serovs’ apartment in St Petersburg was a popular meeting place for famous painters and sculptors, including Nikolai Ge, Mark Antokolsky, and Ilya Repin.”

This nepotism served him well, as it was Antokolsky who recognised the youngster’s talent, delivering him “into the hands of Repin”, who taught and befriended his young colleague: “Repin was in France at the time on a postgraduate assignment from the St Petersburg Academy of Arts, and Serov began attending his studio.” Serov assisted Repin in several large compositions he was doing at the time, drawing the barn that can be seen in the background of Repin’s Send-off of Recruit.

After Repin had taught the boy all he needed to know, his connections secured Serov a place in the Russian Academy of the arts, where he was taught by Pavel Chistiakov, “the only man in the Academy capable of teaching a novice the basic principles of art”.

Although some artists have had humble beginnings, many struggle to make ends meet during their lifetimes and, like Van Gogh, their talents remained “undiscovered” until after their death. Would Serov have reached such dizzying heights were it not for the excellent training he received through his family connections?

Wealth and contacts seem to go a long way in the art world. If you’re looking to be a prize-winning artist, maybe take a leaf out of Serov’s book – a bit of light hobnobbing certainly wouldn’t go amiss.

Quoted text from the illustrated art book Serov, by Parkstone International. Order your print copy or e-book to read more about this extremely talented and well-regarded Russian artist.

Friday, July 27, 2012

Munch ado about nothing

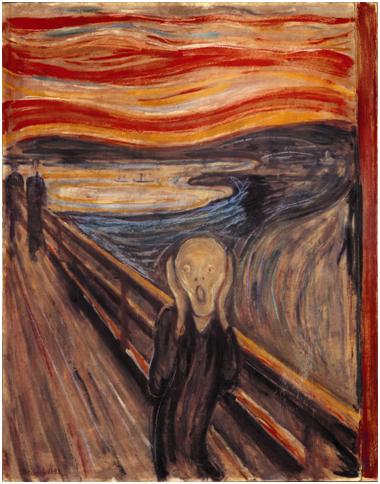

So you think you know Edvard Munch? Think again. That’s the tag-line for the Tate Modern‘s new Munch exhibition, whose premise is that Munch is an under-analysed artist, pigeonholed as a troubled loner and worthy of reassessment. They profess that there were more sides to his personality than just ‘the man who painted The Scream’, and the exhibition seeks to find out what else made him tick through an analysis of the other themes in his work, such as his debilitating eye disease, the theatre and his burgeoning interest in film photography. They implore us to see past the “angst-ridden and brooding Nordic artist who painted scenes of isolation and trauma”, but do people really want to strip off the interesting layers to reveal the normal, everyday Eddie underneath?

Within the art community, it is a dream come true to find another piece of the missing puzzle, to “discover” the man behind the artist and to know exactly what his motives and inspirations were for every piece or artistic period in his life. However, representing the “whole picture” detracts from what made the artist interesting or unique in the first place, or even what makes the paintings so breathtaking. It is scientifically proven* that the longer you spend with a partner, the less interesting they become; in this way, the more you know about the banal aspects of an artist’s life, the less legendary they are. Stick to what makes Munch alluring – a tortured, unloved soul who expresses himself through his harrowing, yet awe-inspiring paintings.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893.

Tempera and crayon on cardboard, 91 x 73,5 cm.

Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo.

It is more than agreeable to believe that Munch painted his masterpieces in an oxymoronic frenzy of despair – catharsis for his traumatic youth. But this new wave of “understanding” of every aspect of Munch’s life has led to an interpretation that Munch was well aware of the techniques and visual effects that he employed to such devastating effect, and that it was in fact the commercial viability of reproducing a popular painting that drove Munch to rework his favoured themes time and again. If this is the case, then Munch knew how to play us like a fiddle.

Have these people learned nothing from Munch? Angst sells, big time, and if the Tate wants to increase its footfall, it too should sell out and give the people what they want – a slice of the despondent Munch we think we know. I’ve heard that The Scream is supposed to be a pretty good painting...

Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye is showing at the Tate Modern from 28 June – 14 October 2012. Or, to view some of Munch’s popular works (including The Scream), why not try this Munch art e-book?

*it is not really scientifically proven.

Friday, July 13, 2012

Hopper: drudgery and dysthymia

Hopper has to be the least fitting name for an artist as misanthropic as he. He was an introvert with a wry sense of humour, who would fall into great periods of melancholy, pierced on occasion by flashes of brilliant inspiration. But great art comes from great depression. Take the obvious example, Van Gogh, whose struggle with manic depression led him to paint some of the most celebrated art in history. Other, lesser known depressives included William Blake, Gauguin, Pollock, Miró, and even Michelangelo. I’m not saying you have to be depressed to be an artist, but it helps. The irony is that Hopper was one of the few artists whose careers actually flourished during the Great Depression.

Edward Hopper, Eleven A.M., 1926.

Oil on canvas, 71.3 x 91.6 cm.

Smithsonian Institution, Hirshhorn

Museum and Sculpture Garden,

Washington, D.C.

It takes a pessimist to be able view life through a realist lens. Hopper’s work strikes a chord with people not because it gives them a cheery nod to the future, but because it reflects the banality, solitude, loneliness and boredom of moments in our own lives, and says to us: “Hey, you know what? It’s ok if you want to sit in your knickers and stare out of the window all day − people did it in the 1920s too!” For many of us, it reflects the poignancy of relationships, and the bitterness of a break-up. If there is a couple, the intimacy has gone, and each is resigned to the fate of either an imminent split or a life of regrets, each wallowing in their own well of ‘what ifs’.

Edward Hopper, Summer in the City, 1949.

Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 76.2 cm.

Berry-Hill Galleries, Inc., New York.

Think you can create world-class art with a canvas, some paints, and optimism alone? Then think again, preferably in your underwear, staring into space.

You can still see Hopper’s works at the Hopper exhibition, at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, until 16 September 2012. Get to know the artist, and what made him tick, with this detailed art book about Hopper’s life and times.

Wednesday, July 4, 2012

Romance us please, Renoir

Life is far from peachy at the moment in the West: stagnating economies, rising unemployment, a proliferation of extreme right-wing ideologies, decreasing social mobility, and the oxymoronically-phrased ‘negative growth’ all give rise to a rather bleak outlook. Is it any wonder that, whilst many young Westerners escape to the East in search of more prosperous times, those left on the sinking ship turn to drink, drugs, and dangerous driving in order to forget about the futility of their futures?

I may be exaggerating a little but, in these times, many of us are looking for a distraction, or getting ourselves fitted for rose-tinted glasses. This is where the Museum of Fine Arts Boston has been shrewd. The current climate is an ideal time to display three of Renoir’s pink-cheeked, quivering-bosomed Mesdames in the arms of wandering-handed Messieurs, deep in the throes of love, pressing themselves against each other as if they are the only two people in the ballroom/park/countryside.

From left to right:

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Dance in the City, 1883. Oil on canvas, 180 x 90 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Dance in the Country, 1883. Oil on canvas, 180 x 90 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Dance at Bougival, 1883. Oil on canvas, 181.9 x 98.1 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This is for two reasons; firstly, it harks back to a simpler time, where their only care in the world was to drink as much wine and to make as much merriment as possible, and possibly to catch the eye of a potential suitor. Secondly, it represents a much more innocent and romantic type of romance. Renoir depicts the thrill of the dance, the anticipation that somewhere, under half a dozen petticoats and a very confusing contraption masquerading as underwear, there is something worth the trouble to undress for. Grinding to Dubstep in high heels and a tea towel just doesn’t convey the same... tenderness.

This exhibition should come with a disclaimer: you may go in an embittered, old, shrivelled-up hag with a charcoal heart, but you will come out drooling like a teenage girl, who has just discovered that boys really don’t have cooties after all. And maybe, maybe that’s just what we need right now.

If you want to dance with Renoir in person*, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston will be displaying these three paintings until 3 September. If you can’t make it to Boston, you can drool over Renoir from afar with this art book, available in both print and digital formats, including many more of his impressive impressionist paintings.

*There is no guarantee that Renoir will be there in person.

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

So Peculiarly English: topographical watercolours

English watercolours are not peculiar in any way, shape or form. In fact, they are the opposite, the very essence of banality. The only peculiar thing about them is that the English were the only ones to bother with them, and that they insisted on doing it for so long.

Not only that, but topographical landscapes, so you can see the English countryside in all its... dreariness. Early topographical watercolours, writes Bruce MacEvoy, were “primarily used as an objective record of an actual place in an era before photography”; as land surveillance maps, for military strategy (to help us out with our colonising), for the mega-rich to show off their wealthy estates (built in all probability with money from the slave trade), and for archaeological digs, for when we wanted to have a record of whose lands we had already pillaged. Doesn’t it feel great to be English?

John Constable, Stonehenge, 1835. Watercolour on paper, 38.7 x 59.7 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

When we weren’t painting watercolours to celebrate our upper classes’ moral ineptitude, we were depicting scenes of England’s lush greenery, her rolling hills, picturesque villages and rocky coastline. Or rather, Turner, Constable and Gainsborough were. People can’t get enough of their tedious seascapes and landscapes, as if they’ve never seen a tree or a rock before in their lives. The only redeeming feature of Turner is that apparently he once had himself "tied to the mast of a ship in order to experience the drama" of the elements during a storm at sea, which a great example of English eccentricity right there.

J.M.W. Turner, Warkworth Castle, Northumberland – thunder storm approaching at sunset, 1799.

Watercolour on white paper, 52.1 x 74.9 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, U.K.

Forget the 427 identical paintings of abbeys and vales, heaths and lakes; I’d rather see something truly peculiar, like a painting of Turner tied to a mast of a sinking ship. Then, and only then, would I come to your watercolour exhibition.

If, unlike me, you have a great love for the topographical landscapists of yore, get down to the V&A for their exhibition ‘So Peculiarly English: topographical watercolours’ (from the 7th June 2012 - 1st March 2013). Read up on a classic English painter before (or after) your visit with this Turner ebook, or find more art you'll love on the Ebook-Gallery.

Monday, May 21, 2012

Contre le bien-pensant...

A priori pas grand chose, et pourtant... : Villon Pape des artistes maudits, assassin à ses heures et poète-bagarreur, Pasolini filmant la chair avec délices et tué sur une plage, Courier le séducteur-soldat, brillant helléniste et assassin assassiné et enfin Le Caravage, enfant-maudit de l’Histoire de l’art, mort d’épuisement et peintre de la chair et du désir...

Vous l’aurez compris, la subversion est ici le maître-mot. Ceux qui pensaient que c’était le xxe siècle qui avait inventé l’anti-conformisme, qu’ils lisent –entre autres- les écrits de Villon ou de Courier, qu’ils regardent les toiles de Le Caravage et les films de Pasolini...

On considère souvent Le Caravage comme étant l’inventeur de l’éclairage cinématographique... Ci-dessous une capture d’écran de Teorema, film réalisé en 1968, et un détail de Judith et Holopherne, toile peinte en 1597-1600. Jugez-en par vous même...

« Et le Verbe s’est fait chair »... Entre un peintre mêlant de manière très subversive la religion et la sensualité (Saint-Jean Baptiste, peint vers 1600) et un cinéaste amoureux de l’excès et de la décadence (Teorema, Œdipe Roi, Le Décameron), difficile de trancher lequel des deux a le mieux illustré cette phrase extraite de la Bible...

Bousculant la rigueur morale de leur époque, ces artistes sulfureux laissent leur désir et leur passion s’exprimer tant dans leur vie que dans leur œuvre.

Monday, May 14, 2012

Bosch and his Moral High Horse

Using triptychs and diptychs, Bosch was able to conduct religious narratives through his art. Among his most famous is The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1480-1505) – was Bosch really as stern a Christian as demonstrated in this painting?

At first glance, you’d be forgiven for thinking the scene is a whimsical child’s fairytale. But closer inspection reveals the heavenly and hellish intricate details, embodying both ecstasy and despair.

To me, this is a warning from Bosch’s moral high horse. The story of the Fall of Man. On the left panel (the start of the story), God is bringing together Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The large middle piece shows an orgy of indulgence – humanity acting with free will, engaging in ultimate pleasures. The right reveals the misery of the depths of hell – the consequences of man’s sin: God’s awesome wrath (prompted of course at the start, by Evil Eve).

Some scholars disagree that Bosch was a religious zealot, claiming instead that the tender colours he uses and the beauty of the scene means he can’t possibly have deemed them as sinners. More controversially, it has even been pointed out that his use of ‘hairy’ figures (figures coated in a layer of brown fur) in the middle panel could be indicative of his heretical view of evolution. Some art historians argue they are simply an imagined alternative to our civilised life. What do you think?

Explore the mysteries of Bosch along with other artists at the Tracing Bosch and Bruegel. Four Paintings Magnified exhibition, showing at the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen until 21st October 2012. If you can’t make the exhibition, but want some more information about Bosch and his art, find all you want and more in this lavishly-illustrated Bosch ebook.

Thursday, May 10, 2012

The Self-Indulgence of the Self-Portrait

Self-Portraits are the epicentre of the Metropolitan Museum's current exhibition: ‘Rembrandt and Degas: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’, presenting early self-portraits by the artists side by side for the first time. Featured below: left, Rembrandt van Rijn, Sheet of Studies with Self-Portrait (detail), 1630-1634 and right, Edgar Degas, Self-Portrait (detail), c. 1855-1857:

With the mass production of improved glass mirrors, the Early Renaissance in the mid-15th century saw a wave of self-portraits amongst painters, sculptors, and printmakers alike. A range of self-depictions were produced, from the humble sketch to extravagant biblical scenes, featuring, you guessed it, themselves. Francisco de Zurbarán’s 17th century painting Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross is widely believed to picture himself as St Luke:

It is said that self-portraiture requires a great deal of artistic skill and self-awareness, while exposing one’s own vulnerabilities as both an artist and subject. But how accurate were these self-portraits?

I don’t claim any validity in comparing such a practice in the 15th century to today – photography means there is less need to spend months and years nurturing pictorial evidence of one’s own appearance for the sake of PR.

But producing such work in the 21st century would likely bring about accusations of self-obsession or even criticism for stretching the truth of our own good looks – was this really much different in the 15th century? The temptation to adjust the odd flaw must remain rife in such a practice – a slightly smaller nose or an eradicated mole can be yours at the mere flick of a brush.

Art critics have noted that a trait common to female self-portraits is that they are featured in much smarter attire than they would probably actually be painting in, perhaps indicating some deviance from the mirror image they saw before them. For example, this is a self-portrait by Adelaide Labille-Guiard, Self-Portrait with Two Pupils 1785 – would you want to splash your watercolours on that finery?

Self-portraits also range to the rather more controversial, such as those of Egon Schiele’s collection of self-depictions, which have led to countless medical diagnoses of his mental and sexual health. By this measure, self-portraits are more than paintings; they also provide insight into the artists themselves.

However, reminiscent of the Facebook profile picture (blasphemous!), self-portraits are, and have always been, what the artist wants us to see of them. This is what they would like us to perceive of their personality and character, which by human nature is likely to differ from who they actually were.

Self-portraits provide a fascinating angle on a work of art. We can undoubtedly take a lot more from a self-portrait than we can from one man’s portrait of another, but can we really believe what they convey?

For more information about the exhibition, please visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art's website. For high quality ebooks about Schiele, Degas and a host of other legendary artists, visit ebook-gallery.com.

Caravaggio and Pasolini: Kindred Spirits

Caravaggio’s fine art is accredited with the invention of cinematic lighting – the dramatic contrast of dark and light, the minute detail of the human figure and the intimate reveal of every quirk and blemish feature in all of his pieces. His work is surely the closest we can get to looking at a photograph of the 16th century. Pasolini, equally misunderstood in his lifetime because of his extreme political views, produced some of the most shocking films of the 20th century.

Revolutionary, homosexual and willing to cause a stir, the eerie likeness of their backgrounds (which both remain matters of conjecture) perhaps influenced the similarly dark, stark direction of their work, which typically oozed with as much disdain as it did provocation.

While comparisons between fine art and film can be ambiguous, the dramatic lighting both artists regularly adopted is an undeniable common denominator, as can be seen in a screenshot of Pasolini’s film Teorema (1968), left, and Caravaggio’s masterpiece Judith and Holofernes (1597 - 1600), right:

Caravaggio and Pasolini tended to enjoy the company of the outcasts of society, who they used as models for their work. Unlike his contemporaries, Caravaggio often used ‘common’ people as historic, religious, and wealthy figures, such as Sleeping Cupid (1608), in which a sleeping child is depicted as Cupid (below). Pasolini, similarly, embraced the poor and honest characters from rural Italy, often choosing to use country dialects in his films, rather than mainstream Italian language:

The techniques employed by Pasolini and Caravaggio shed light on a darker side of humanity, one that is real, graphic and well out of range of the popular culture of their times. The artists, three hundred years apart, have evidently reached a mutual understanding of the human condition.